2022 CORRINA MEHIEL FELLOW

2025 – 2026 RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT FELLOW

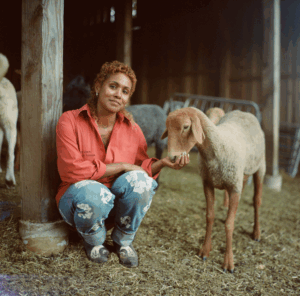

Meet brontë (they/them): is a black-boricua transdisciplinary ritual artist, shepherd, minister and cultural worker. their theological praxis is an intergenerational prayer to resanctify labor with land through rebuking the hauntings slavery has had on our precious relations with earth-rooted ritual and craft. brontë’s ministry is committed to re-ecologizing the roots of pastoral care — as shepherds who paid attention to the earth, followed the wisdom of their rhythms and patterns and through that devotional awareness received prophetic instructions for liberation.

the prayer of brontë’s life is to support safe and hilarious bedside care through climate collapse. they don’t know if we will get to the “other side” but are interested in the quality of tenderness, attention, awe-fullness, and miracles we can offer to each other and the earth on the path of presence. they care for the crossroads of attending to black health/imagination, commemorative justice (Free Egunfemi) and hospicing the shit that hurts black folks and the earth through serving as artistic director for bakiné ritual arts studio (FKA Lead to Life) and adult programs director/educator for ancestral arts skills and nature-connection school Weaving Earth.

they are currently co-conjuring an absurdist opera with esperanza spalding about a frequency that can disarm. they are practicing pastoral care (in an ecological and ministerial sense) as a co-director of The School for Inclement Weather in Kashia Pomo territory in northern California. brontë is currently an MDiv candidate at Duke Divinity. mostly, brontë is up to the sweet tender rhythm of quotidian black queer-lifemaking, ever-committed to humor & liberation, ever-marked by grief at the distance made between us and all of life —

On the Corrina Mehiel Fellowship:

S: How would you describe your community and what sort of encounters with your work do you hope your community might experience?

b: I would describe my community as Black diasporic peoples and Black places. The ways Black folks are in coterminous relationships with their environments–specifically the ways that Black people are impacted in the wake of harm to land and also how the land is affected by the harm inflicted upon Black people.

I have experienced those patterns in many places where I have lived and where my work/attention has been situated–in Atlanta where I’m from, in Oakland where I moved to in 2017, in Puerto Rico/Boríken, which is my ancestral land. Right now my community is also deeply more-than-human because I’ve moved outside of a city, so I’m also in community now with goats and sheep and alpaca and chickens and forest. I am here to support protecting these lands, traditions and the folks indigenous to this land–especially now that Black and Indigenous liberation are tied up with one another.

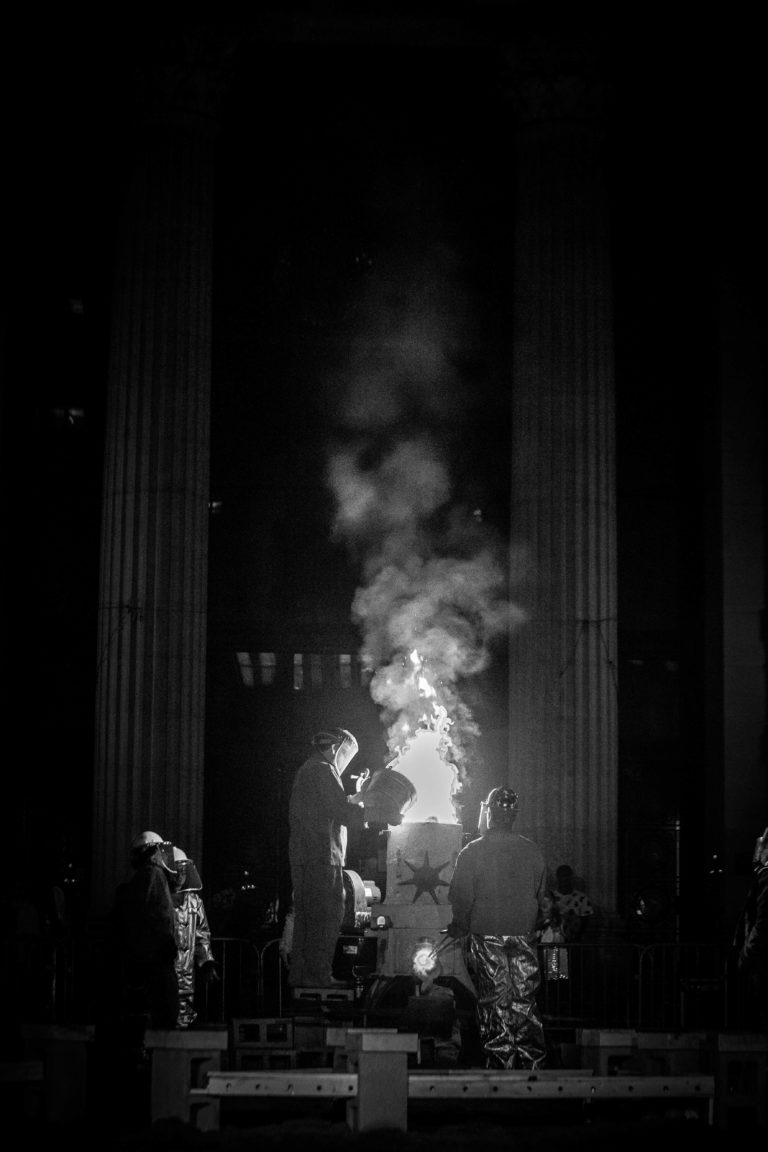

I hope through my work that my communities get to experience the sovereignty of their attention. I think a lot of my work is thinking about how to support encounters with the miraculous — to instigate experiences that offer the wisdom that access to our attention permits us to be encountered by miracles. My miracle work has primarily been situated through my practice with public ceremonies and melting guns into otherwise. Now with S.O.U.R.C.E. and in relationship with my partner who works with prescribed fire, I’m thinking, “How do I support the rehabilitation of witnessing source fire, prescribed fire, through indigenous cultural burning? How do I facilitate the fires that are regenerative and resourceful?”

S: What role does curiosity play in your work and what are you curious about exploring in the year to come?

b: Curiosity is at the core of my practice. Childlike curiosity and play guides my relationship with my attention to re-encounter the land, especially as a descendant of enslaved black folks where the trauma of enslavement separated us from the land and created a complex relationship to the earth. Curiosity heals my relationship with the earth.

Being willing to observe and pay attention even if I don’t know the names of certain birds or all of the plants that I’m seeing is healing. The muscle of curiosity offers; Can I build this relationship if I don’t know the white scientific names of all these things? Can I still be close? Can I have a relationship on my own terms?

In the years to come and specifically this year, my curiosity is arcing towards regenerative grazing, working with sheep and goats, moving toward shepherding. I’m curious about how that’s going to change my art practice, especially around collaborating with their wool, fleece, milk, soap, spirits, humor, etc. I’m being drawn toward black diasporic fiber traditions and ritual garments. I know that relationship with those more-than-human kin is going to deeply change my craft as well.